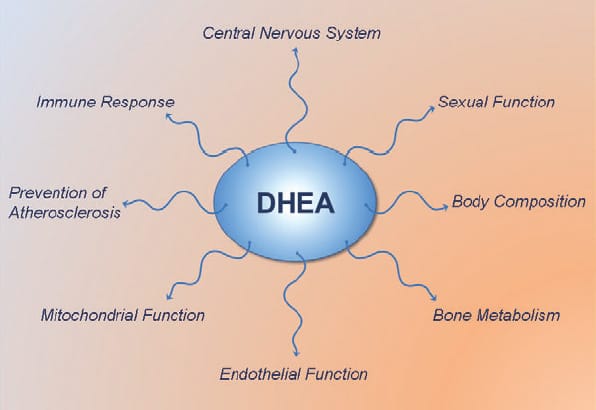

DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone) is most known for being a pro-hormone which in the body gets converted to testosterone and estrogen. It is a long held view that DHEA exerts all its effects via conversion to testosterone and estrogen. However, recent studies show that DHEA also has several interesting non-hormonal actions…

DHEA 101

DHEA is produced mainly by the adrenal cortex, and is rapidly sulfated by sulfotransferases into DHEA-S. DHEA and its sulfated form DHEA-S is the most abundant steroid (pro)hormone circulating in the blood stream.[1] The sulfated from of DHEA has a longer half-life in the blood and its levels remain stable throughout the day, are not altered significantly by the menstrual cycle. When getting a blood test for DHEA, the fraction that is routinely measured is therefore DHEA-S. In response to metabolic demand, DHEA-S is rapidly hydrolyzed back to DHEA by sulfatases.

DHEA levels decrease approximately 80% between ages 25 and 75 year.[2, 3] This large decline in DHEA spurred research interest in the possibility that aging related DHEA deficiency may play a role in the deterioration of physiological and metabolic functions with aging, and in the development of chronic diseases.

![DHEA-leves-age]()

How does DHEA really work?

No specific cellular nuclear receptor has been identified for DHEA.[4] Therefore, the actions of DHEA have traditionally been thought to be mediated via conversion to testosterone and estradiol, which in turn activate androgen and estrogen receptors and thereby elicits their effects.[5-7] However, emerging research is showing that the action of DHEA also involves multiple other receptors, and that DHEA and /or its oxygenated metabolites, such as epiandrosterone (EpiA) metabolites.[8, 9]

Increased NO production

One DHEA activated receptor, a cell surface (membrane-bound) receptor, that binds DHEA with high affinity has been identified in the endothelium (blood vessel wall), heart, liver, and kidney.[10-13] This receptor is coupled to eNOS (endothelial nitric oxide synthase) [10-12], the enzyme that activates the synthesis of NO (nitric oxide).[14] Endothelial cells exposed to varying concentrations of DHEA produced dose-dependent increased activation of eNOS and elevated nitrate levels (a bi-product of NO).[10, 12] This activation of eNOS by DHEA was not inhibited by the antagonists of the estrogen, androgen, or progesterone receptors, suggesting that eNOS activation by DHEA was through a very specific receptor for DHEA.[12] Support for this comes from another study demonstrating that DHEA supplementation 50 g/day for 2 months in healthy men aged 58+ years increased cGMP (platelet cyclic guanosine-monophosphate) concentrations, which is a marker of NO production.[15]

DHEA also activates an important vascular endothelial cell signaling pathway (ERK1/2) which plays an important role in vascular function.[16] This, combined with the DHEA induced elevation in NO production could explain the beneficial cardiovascular effects which have been seen in several DHEA supplementation studies in humans; such as improvement in vascular endothelial function, arterial stiffness and insulin sensitivity. [17-20]

The DHEA metabolite: 7-beta EpiA

Another exciting finding is that a 7-beta hydroxylated derivative of DHEA is physiologically active via a putative nuclear receptor.[21-23] It is especially notable that 7-beta-hydroxy-epiandrosterone (EpiA) inhibits COX-2 activity (the same enzyme that is targeted by NSAID) and markedly decreases production of the inflammatory prostaglanding PGE(2).[21, 22] 7-beta-EpiA also stimulates production of the anti-inflammatory prostaglandin PGJ(2).[22] Another study confirmed that 7-beta-EpiA stimulates the production of cell protective (cytoprotective) prostaglandins.[23]

These findings have important implications in health and disease. The inflammatory COX-2/PGE2 pathway is an important contributor to the development of cancer, and suppressing the COX-2/PGE2 pathway is a bona fide target for cancer chemoprevention and therapy.[24] In line with this, it has been speculated that a common factor of cancer and the metabolic syndrome may be low DHEA.[25] Thus, there is a good mechanistic basis for a potential beneficial effect of DHEA in inflammatory conditions and for cancer prevention.

![DHEA-effects]()

Reduced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and elevated IGF-1 action

Levels of inflammatory markers, such as serum amyloid protein A and C-reactive protein, are inversely correlated with DHEA-S levels, suggesting a role for DHEA in attenuating inordinate inflammatory responses.[26] In addition, DHEA inhibits production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and TNF-alpha.[20, 27, 28]

As pro-inflammatory cytokines are known to induce IGF-1 resistance [29], by reducing their production DHEA indirectly may improve the responsiveness to IGF-1. DHEA supplementation also increases absolute levels of IGF-1 [30-35] and DHEA metabolites may stimulate aging cells in the anterior pituitary produce growth hormone (called somatotropes).[36] The stimulatory effect of DHEA on the GH/IGF-1 axis in humans is supported by several DHEA supplementation studies.[32-34, 37]

Reduced cortisol levels

DHEA supplementation lowers cortisol levels, even in young adults.[38-42] While it is still unknown exactly how DHEA exerts its anti-cortisol effect, several mechanisms have been proposed.[43] One speculation is that DHEA down regulates glucocorticoid receptors.[44, 45]

Chronically elevated cortisol levels stimulate development of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, mood disorders and memory impairments.[46-53] Administration of DHEA has been demonstrated to counteract the detrimental effects of cortisol in animals [54-56], and in humans, DHEA and cortisol produce opposing effects on the innate immune system; DHEA enhances while cortisol suppresses immunity.[57]

Lowering of cortisol levels with DHEA supplementation can indirectly provide additional benefits. Cortisol breaks down muscle tissue [58, 59], and suppresses testicular testosterone synthesis via multiple mechanisms. Notably, cortisol exerts a direct inhibitory action on testosterone producing Leydig cells in the testicles [60]. Cortisol also induces leptin resistance [53, 61] and thus may diminish leptin’s stimulatory effects on gonadotropin secretion of LH and FSH [62-64] and consequently diminish the secretion of sex hormones from testicles (testosterone) and the ovary (estrogen). Thus, by lowering cortisol levels, DHEA indirectly might confer several additional beneficial effects.

Improved Cortisol/DHEA ratio

DHEA, by reducing blood cortisol levels and elevating DHEA(S) levels, decreases the cortisol/DHEA ratio, which typically increases with age.[65, 66] This imbalance in the cortisol/DHEA ratio has been demonstrated to possibly contribute to several health derangements.

An increased cortisol:DHEAS ratios may contribute to reduced immunity following physical stress in the elderly[57], and may contribute to the development of cognitive impairment [67, 68] and stress-related psychiatric disorders.[69] The increased ratio of cortisol/DHEA-S is also positively associated with the metabolic syndrome and cancer/all-cause mortality.[70, 71] Thus, improvement of the cortisol/DHEA ratio with DHEA supplementation could help counteract age-related catabolism, metabolic dysfunction and prevent development of chronic disease.

Inhibition of the cortisol amplifier 11beta-HSD1

Cortisol levels in the blood is just one part of the picture. Obese humans and rodents have elevated levels of cortisol inside their fat cells (adipocytes), due to an increased activity of 11beta-HSD1 in adipose tissue.[46, 72-76]

11beta-HSD1 (11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1) is an enzyme that elevates intracellular cortisol levels, irrespective of circulating cortisol levels in the blood, and thereby amplifies cortisol’s fat accumulating actions.[46, 72, 76]

Cause-effect evidence comes from rodent studies showing that transgenic mouse with elevated 11beta-HSD activity have increased cortisol levels in fat cells and develop obesity, expanded visceral (intra-abdominal) fat stores, high blood glucose (hyperglycaemia), blood lipid abnormalities (dyslipidaemia) and hypertension.[77-79] And conversely, pharmacological inhibition of 11beta-HSD1 effectively induces weight loss in obese mice and enhances insulin sensitivity and lowers blood glucose.[80-83]

An increased 11beta-HSD1 activity not promotes expansion of fat stores (especially in the abdominal region) but also contributes to metabolic derangement, which is why 11beta-HSD1 inhibition is an emerging therapeutic target for treatment of obesity, metabolic syndrome and type-2 diabetes.[46, 84-88] DHEA also inhibits 11beta-HSD1 activity in muscle cells, which could be an additional mechanism (on top of simply lowering blood cortisol levels) by which DHEA might prevent cortisol induced insulin resistance and muscle catabolism.[89]

Several studies have demonstrated that DHEA inhibits the activity of 11beta-HSD1 in fat cells from both rodents and humans [90-92], and thereby it counteracts cortisol’s fat storing effect [73, 74]. The inhibitory effect of DHEA on 11beta-HSD1 could be a contributing mechanism to the reduction in total body fat mass [93] and abdominal fat that has been seen with DHEA supplementation.[94]

Bottom Line

While many of the effects of DHEA are mediated via conversion to testosterone and estrogen and activation of the androgen and estrogen receptors, the studies outlined here clearly show that DHEA(S) is biologically active in its own right.

DHEA itself acts through specific cell surface receptors to increase eNOS activity and NO production, and contributes to intracellular signaling through activation of several intracellular messengers. DHEA also suppresses many of the detrimental effects of cortisol in muscle and fat tissue, and increases IGF-1 sensitivity and IGF-1 levels. Thus, it is time to re-evaluate the physiological role of DHEA and appreciate its multifaceted health promoting and potential fat loss actions.

For Additional DHEA info, more articles, videos, etc on DHEA on this site can be found HERE

References:

1. Baulieu, E.E., et al., An Adrenal-Secreted “Androgen”: Dehydroisoandrosterone Sulfate. Its Metabolism and a Tentative Generalization on the Metabolism of Other Steroid Conjugates in Man. Recent Prog Horm Res, 1965. 21: p. 411-500.

2. Orentreich, N., et al., Age changes and sex differences in serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate concentrations throughout adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1984. 59(3): p. 551-5.

3. Orentreich, N., et al., Long-term longitudinal measurements of plasma dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate in normal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1992. 75(4): p. 1002-4.

4. Widstrom, R.L. and J.S. Dillon, Is there a receptor for dehydroepiandrosterone or dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate? Semin Reprod Med, 2004. 22(4): p. 289-98.

5. Engdahl, C., et al., Role of Androgen and Estrogen Receptors for the Action of Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA). Endocrinology, 2014: p. en20131561.

6. Corona, G., et al., Dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation in elderly men: a meta-analysis study of placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2013. 98(9): p. 3615-26.

7. Sirrs, S.M. and R.A. Bebb, DHEA: panacea or snake oil? Can Fam Physician, 1999. 45: p. 1723-8.

8. Webb, S.J., et al., The biological actions of dehydroepiandrosterone involves multiple receptors. Drug Metab Rev, 2006. 38(1-2): p. 89-116.

9. El Kihel, L., Oxidative metabolism of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and biologically active oxygenated metabolites of DHEA and epiandrosterone (EpiA)–recent reports. Steroids, 2012. 77(1-2): p. 10-26.

10. Liu, D. and J.S. Dillon, Dehydroepiandrosterone activates endothelial cell nitric-oxide synthase by a specific plasma membrane receptor coupled to Galpha(i2,3). J Biol Chem, 2002. 277(24): p. 21379-88.

11. Liu, D. and J.S. Dillon, Dehydroepiandrosterone stimulates nitric oxide release in vascular endothelial cells: evidence for a cell surface receptor. Steroids, 2004. 69(4): p. 279-89.

12. Simoncini, T., et al., Dehydroepiandrosterone modulates endothelial nitric oxide synthesis via direct genomic and nongenomic mechanisms. Endocrinology, 2003. 144(8): p. 3449-55.

13. Komesaroff, P.A., Unravelling the enigma of dehydroepiandrosterone: moving forward step by step. Endocrinology, 2008. 149(3): p. 886-8.

14. Duckles, S.P. and V.M. Miller, Hormonal modulation of endothelial NO production. Pflugers Arch, 2010. 459(6): p. 841-51.

15. Martina, V., et al., Short-term dehydroepiandrosterone treatment increases platelet cGMP production in elderly male subjects. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 2006. 64(3): p. 260-4.

16. Liu, D., et al., Dehydroepiandrosterone stimulates endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis through extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2-mediated mechanisms. Endocrinology, 2008. 149(3): p. 889-98.

17. Kawano, H., et al., Dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation improves endothelial function and insulin sensitivity in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2003. 88(7): p. 3190-5.

18. Weiss, E.P., et al., Dehydroepiandrosterone replacement therapy in older adults improves indices of arterial stiffness. Aging Cell, 2012. 11(5): p. 876-84.

19. Petrie, J.R., et al., Endothelial nitric oxide production and insulin sensitivity. A physiological link with implications for pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. Circulation, 1996. 93(7): p. 1331-3.

20. Weiss, E.P., et al., Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) replacement decreases insulin resistance and lowers inflammatory cytokines in aging humans. Aging (Albany NY), 2011. 3(5): p. 533-42.

21. Le Mee, S., et al., 7beta-Hydroxy-epiandrosterone-mediated regulation of the prostaglandin synthesis pathway in human peripheral blood monocytes. Steroids, 2008. 73(11): p. 1148-59.

22. Hennebert, O., et al., Anti-inflammatory effects and changes in prostaglandin patterns induced by 7beta-hydroxy-epiandrosterone in rats with colitis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 2008. 110(3-5): p. 255-62.

23. Davidson, J., E. Wulfert, and D. Rotondo, 7beta-hydroxy-epiandrosterone modulation of 15-deoxy-delta12,14-prostaglandin J2, prostaglandin D2 and prostaglandin E2 production from human mononuclear cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 2008. 112(4-5): p. 220-7.

24. Greenhough, A., et al., The COX-2/PGE2 pathway: key roles in the hallmarks of cancer and adaptation to the tumour microenvironment. Carcinogenesis, 2009. 30(3): p. 377-86.

25. Howard, J.M., Common factor of cancer and the metabolic syndrome may be low DHEA. Ann Epidemiol, 2007. 17(4): p. 270.

26. Sondergaard, H.P., L.O. Hansson, and T. Theorell, The inflammatory markers C-reactive protein and serum amyloid A in refugees with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Chim Acta, 2004. 342(1-2): p. 93-8.

27. Ramirez, J.A., et al., Syntheses of immunomodulating androstanes and stigmastanes: comparison of their TNF-alpha inhibitory activity. Bioorg Med Chem, 2007. 15(24): p. 7538-44.

28. Straub, R.H., et al., Serum dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulfate are negatively correlated with serum interleukin-6 (IL-6), and DHEA inhibits IL-6 secretion from mononuclear cells in man in vitro: possible link between endocrinosenescence and immunosenescence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1998. 83(6): p. 2012-7.

29. O’Connor, J.C., et al., Regulation of IGF-I function by proinflammatory cytokines: at the interface of immunology and endocrinology. Cell Immunol, 2008. 252(1-2): p. 91-110.

30. Weiss, E.P., et al., Dehydroepiandrosterone replacement therapy in older adults: 1- and 2-y effects on bone. Am J Clin Nutr, 2009. 89(5): p. 1459-67.

31. Igwebuike, A., et al., Lack of dehydroepiandrosterone effect on a combined endurance and resistance exercise program in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2008. 93(2): p. 534-8.

32. Genazzani, A.D., et al., Oral dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation modulates spontaneous and growth hormone-releasing hormone-induced growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 secretion in early and late postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril, 2001. 76(2): p. 241-8.

33. Morales, A.J., et al., Effects of replacement dose of dehydroepiandrosterone in men and women of advancing age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1994. 78(6): p. 1360-7.

34. Morales, A.J., et al., The effect of six months treatment with a 100 mg daily dose of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on circulating sex steroids, body composition and muscle strength in age-advanced men and women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 1998. 49(4): p. 421-32.

35. Villareal, D.T., J.O. Holloszy, and W.M. Kohrt, Effects of DHEA replacement on bone mineral density and body composition in elderly women and men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 2000. 53(5): p. 561-8.

36. Iruthayanathan, M., Y.H. Zhou, and G.V. Childs, Dehydroepiandrosterone restoration of growth hormone gene expression in aging female rats, in vivo and in vitro: evidence for actions via estrogen receptors. Endocrinology, 2005. 146(12): p. 5176-87.

37. Casson, P.R., et al., Postmenopausal dehydroepiandrosterone administration increases free insulin-like growth factor-I and decreases high-density lipoprotein: a six-month trial. Fertil Steril, 1998. 70(1): p. 107-10.

38. Genazzani, A.R., et al., Long-term low-dose oral administration of dehydroepiandrosterone modulates adrenal response to adrenocorticotropic hormone in early and late postmenopausal women. Gynecol Endocrinol, 2006. 22(11): p. 627-35.

39. Kroboth, P.D., et al., Influence of DHEA administration on 24-hour cortisol concentrations. J Clin Psychopharmacol, 2003. 23(1): p. 96-9.

40. Alhaj, H.A., A.E. Massey, and R.H. McAllister-Williams, Effects of DHEA administration on episodic memory, cortisol and mood in healthy young men: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2006. 188(4): p. 541-51.

41. Stomati, M., et al., Six-month oral dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation in early and late postmenopause. Gynecol Endocrinol, 2000. 14(5): p. 342-63.

42. McQuade, R. and A.H. Young, Future therapeutic targets in mood disorders: the glucocorticoid receptor. Br J Psychiatry, 2000. 177: p. 390-5.

43. Kalimi, M., et al., Anti-glucocorticoid effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA). Mol Cell Biochem, 1994. 131(2): p. 99-104.

44. Kalimi, M., J. Opoku, and R.e.a. Lu, Studies of the biochemical action and mechanism of dehydroepiandrosterone. , in The biologic role of dehydroepiandrosterone, M. Kalimi and W. Regelson, Editors. 1990: Walter de Gruyter, New York,. p. pp 397-404.

45. Crudo, D., Downregulation of glucocorticoid receptors by dehydroepiandrosterone. 71st Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society, Seattle, WA, p 386 (Abst), 1989.

46. Wamil, M. and J.R. Seckl, Inhibition of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 as a promising therapeutic target. Drug Discov Today, 2007. 12(13-14): p. 504-20.

47. Stimson, R.H. and B.R. Walker, Glucocorticoids and 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Minerva Endocrinol, 2007. 32(3): p. 141-59.

48. Viau, V., Functional cross-talk between the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal and -adrenal axes. J Neuroendocrinol, 2002. 14(6): p. 506-13.

49. Pasquali, R., et al., The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2006. 1083: p. 111-28.

50. Boscaro, M., G. Giacchetti, and V. Ronconi, Visceral adipose tissue: emerging role of gluco- and mineralocorticoid hormones in the setting of cardiometabolic alterations. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2012. 1264: p. 87-102.

51. Dallman, M.F., et al., Minireview: glucocorticoids–food intake, abdominal obesity, and wealthy nations in 2004. Endocrinology, 2004. 145(6): p. 2633-8.

52. Fraser, R., et al., Cortisol effects on body mass, blood pressure, and cholesterol in the general population. Hypertension, 1999. 33(6): p. 1364-8.

53. Ur, E., A. Grossman, and J.P. Despres, Obesity results as a consequence of glucocorticoid induced leptin resistance. Horm Metab Res, 1996. 28(12): p. 744-7.

54. Daynes, R.A., D.J. Dudley, and B.A. Araneo, Regulation of murine lymphokine production in vivo. II. Dehydroepiandrosterone is a natural enhancer of interleukin 2 synthesis by helper T cells. Eur J Immunol, 1990. 20(4): p. 793-802.

55. Daynes, R.A., et al., Regulation of murine lymphokine production in vivo. III. The lymphoid tissue microenvironment exerts regulatory influences over T helper cell function. J Exp Med, 1990. 171(4): p. 979-96.

56. Browne, E.S., et al., Dehydroepiandrosterone: antiglucocorticoid action in mice. Am J Med Sci, 1992. 303(6): p. 366-71.

57. Butcher, S.K., et al., Raised cortisol:DHEAS ratios in the elderly after injury: potential impact upon neutrophil function and immunity. Aging Cell, 2005. 4(6): p. 319-24.

58. Lofberg, E., et al., Effects of high doses of glucocorticoids on free amino acids, ribosomes and protein turnover in human muscle. Eur J Clin Invest, 2002. 32(5): p. 345-53.

59. Rooyackers, O.E. and K.S. Nair, Hormonal regulation of human muscle protein metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr, 1997. 17: p. 457-85.

60. Dong, Q., et al., Rapid glucocorticoid mediation of suppressed testosterone biosynthesis in male mice subjected to immobilization stress. J Androl, 2004. 25(6): p. 973-81.

61. Zakrzewska, K.E., et al., Glucocorticoids as counterregulatory hormones of leptin: toward an understanding of leptin resistance. Diabetes, 1997. 46(4): p. 717-9.

62. Barb, C.R., J.B. Barrett, and R.R. Kraeling, Role of leptin in modulating the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and luteinizing hormone secretion in the prepuberal gilt. Domest Anim Endocrinol, 2004. 26(3): p. 201-14.

63. Yu, W.H., et al., Role of leptin in hypothalamic-pituitary function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1997. 94(3): p. 1023-8.

64. Zieba, D.A., M. Amstalden, and G.L. Williams, Regulatory roles of leptin in reproduction and metabolism: a comparative review. Domest Anim Endocrinol, 2005. 29(1): p. 166-85.

65. Otte, C., et al., A meta-analysis of cortisol response to challenge in human aging: importance of gender. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2005. 30(1): p. 80-91.

66. Stein-Behrens, B.A. and R.M. Sapolsky, Stress, glucocorticoids, and aging. Aging (Milano), 1992. 4(3): p. 197-210.

67. Kalmijn, S., et al., A prospective study on cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, and cognitive function in the elderly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 1998. 83(10): p. 3487-92.

68. Lupien, S.J., et al., Cortisol levels during human aging predict hippocampal atrophy and memory deficits. Nat Neurosci, 1998. 1(1): p. 69-73.

69. Garner, B., et al., Cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone-sulphate levels correlate with symptom severity in first-episode psychosis. J Psychiatr Res, 2011. 45(2): p. 249-55.

70. Phillips, A.C., et al., Cortisol, DHEA sulphate, their ratio, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the Vietnam Experience Study. Eur J Endocrinol, 2010. 163(2): p. 285-92.

71. Phillips, A.C., et al., Cortisol, DHEAS, their ratio and the metabolic syndrome: evidence from the Vietnam Experience Study. Eur J Endocrinol, 2010. 162(5): p. 919-23.

72. Walker, B.R., Extra-adrenal regeneration of glucocorticoids by 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1: physiological regulator and pharmacological target for energy partitioning. Proc Nutr Soc, 2007. 66(1): p. 1-8.

73. Rask, E., et al., Tissue-specific dysregulation of cortisol metabolism in human obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2001. 86(3): p. 1418-21.

74. Rask, E., et al., Tissue-specific changes in peripheral cortisol metabolism in obese women: increased adipose 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2002. 87(7): p. 3330-6.

75. Lindsay, R.S., et al., Subcutaneous adipose 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 activity and messenger ribonucleic acid levels are associated with adiposity and insulinemia in Pima Indians and Caucasians. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2003. 88(6): p. 2738-44.

76. Wake, D.J., et al., Local and systemic impact of transcriptional up-regulation of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in adipose tissue in human obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2003. 88(8): p. 3983-8.

77. Agarwal, A.K., Cortisol metabolism and visceral obesity: role of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type I enzyme and reduced co-factor NADPH. Endocr Res, 2003. 29(4): p. 411-8.

78. Masuzaki, H., et al., A transgenic model of visceral obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Science, 2001. 294(5549): p. 2166-70.

79. Masuzaki, H., et al., Transgenic amplification of glucocorticoid action in adipose tissue causes high blood pressure in mice. J Clin Invest, 2003. 112(1): p. 83-90.

80. Hermanowski-Vosatka, A., et al., 11beta-HSD1 inhibition ameliorates metabolic syndrome and prevents progression of atherosclerosis in mice. J Exp Med, 2005. 202(4): p. 517-27.

81. Park, J.S., et al., Anti-diabetic and anti-adipogenic effects of a novel selective 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 inhibitor in the diet-induced obese mice. Eur J Pharmacol, 2012. 691(1-3): p. 19-27.

82. Alberts, P., et al., Selective inhibition of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 decreases blood glucose concentrations in hyperglycaemic mice. Diabetologia, 2002. 45(11): p. 1528-32.

83. Alberts, P., et al., Selective inhibition of 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 improves hepatic insulin sensitivity in hyperglycemic mice strains. Endocrinology, 2003. 144(11): p. 4755-62.

84. Anagnostis, P., et al., 11beta-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 inhibitors: novel agents for the treatment of metabolic syndrome and obesity-related disorders? Metabolism, 2013. 62(1): p. 21-33.

85. Tomlinson, J.W., 11Beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in human disease: a novel therapeutic target. Minerva Endocrinol, 2005. 30(1): p. 37-46.

86. Morton, N.M. and J.R. Seckl, 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and obesity. Front Horm Res, 2008. 36: p. 146-64.

87. Joharapurkar, A., et al., 11beta-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1: potential therapeutic target for metabolic syndrome. Pharmacol Rep, 2012. 64(5): p. 1055-65.

88. Masuzaki, H. and J.S. Flier, Tissue-specific glucocorticoid reactivating enzyme, 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11 beta-HSD1)–a promising drug target for the treatment of metabolic syndrome. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord, 2003. 3(4): p. 255-62.

89. Whorwood, C.B., et al., Regulation of glucocorticoid receptor alpha and beta isoforms and type I 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase expression in human skeletal muscle cells: a key role in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance? J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2001. 86(5): p. 2296-308.

90. Apostolova, G., et al., Dehydroepiandrosterone inhibits the amplification of glucocorticoid action in adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2005. 288(5): p. E957-64.

91. Tagawa, N., et al., Alternative mechanism for anti-obesity effect of dehydroepiandrosterone: possible contribution of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 inhibition in rodent adipose tissue. Steroids, 2011. 76(14): p. 1546-53.

92. McNelis, J.C., et al., Dehydroepiandrosterone exerts antiglucocorticoid action on human preadipocyte proliferation, differentiation, and glucose uptake. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2013. 305(9): p. E1134-44.

93. Libe, R., et al., Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) supplementation on hormonal, metabolic and behavioral status in patients with hypoadrenalism. J Endocrinol Invest, 2004. 27(8): p. 736-41.

94. Villareal, D.T. and J.O. Holloszy, Effect of DHEA on abdominal fat and insulin action in elderly women and men: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 2004. 292(18): p. 2243-8.

DHEA – does it have any beneficial non-hormonal effects? is a post from: The Final Frontier In Bodybuilding , Fat Loss, Health & Fitness